CTRL/ART/DISCRETE

Leveraging new technology & traditional methods as problem-solving tools in the production of a $62K feature film

Since Thanksgiving, we have seen the release of Veo 2 (Google), Sora (OpenAI), Frames (RunwayML), Ray2 (Luma), Pika 2.1, Multi-Image Reference (Kling), and even a Netflix AI video model.

Previous months gave us generative AI studio announcements, “clean” video model claims, and the plot of an entire mainstream movie designed around a deepfake de-aging device.

Three weeks ago, The Brutalist received 10 Academy Award nominations in the same breath that the film came under fire for having used AI in its production—Ukrainian AI startup Respeecher leveraged a bespoke Hungarian voice model to augment actors’ performances of the notoriously challenging language.

At the end of January, both Variety (alongside Adobe) and Dropbox (with Indiewire) hosted AI filmmaking panel discussions at the Sundance Film Festival.

Now, we know The Brutalist was not the only Oscar-nominated film to use AI: A Complete Unknown, Dune: Part Two, and Emilia Perez all employed some form of the technology (in addition to recent mainstream movies like Here, Mad Max: Furiosa, Elvis, Alien: Romulus, and Maria).

In the future, the Academy may mandate the disclosure of AI use for any film submitted for consideration.

Today, I am contributing to the canon.

Here, I outline the artificial intelligence, emerging technology, and unconventional post-production processes employed in the making of Under the Influencer, a feature film with an initial shooting budget of $62,000.

This piece will provide a cursory summary of many instances of AI in the film—it will not go into granular detail or provide step-by-step breakdowns of processes. I may eventually publish more in-depth walkthroughs if there is interest.

THE MOTIVATION

OH PRACTICAL GUIDANCE, WHERE ART THOU?

I have been repeatedly frustrated by the lack of practical knowledge shared in this space.

The aforementioned Sundance AI panel hosted by Dropbox promised to discuss how “filmmakers can ethically use AI,” but only the documentarians on the panel shared actionable knowledge and/or practices employed in past or current projects.

While one could trip and stumble over vast repositories of AI-generated memes, movie trailers, spec ads, quaint concepts, and weirdo lip-synched short films, there are few case studies available to traditional, live-action filmmakers who are interested in experimenting with new technology.

Even less guidance exists for legacy filmmakers looking to ethically leverage new technological advancements.

Fortunately, Adobe’s Firefly release heralds a sea change: the promise of licensed, IP-safe, and/or public domain training data only.

Still, until IP-safe video models are the norm—and until the companies training them have proven their training data is legally sourced—it is crucial to examine the ethical line of AI use.

ART AND OWNERSHIP

Microbudget feature Under the Influencer is, above all, about art.

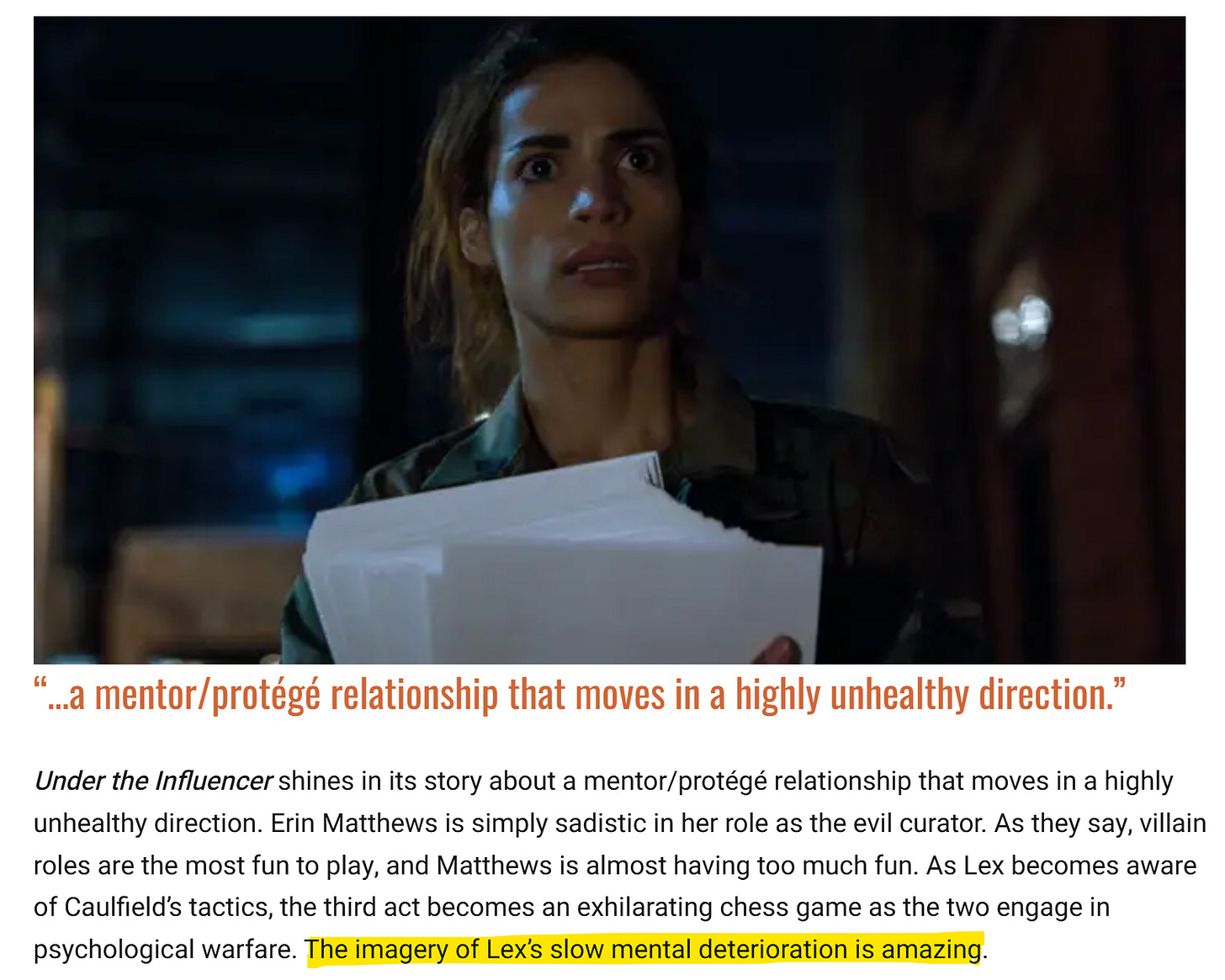

The film’s narrative centers Lex Carre, a digital artist who processes her mental health struggles through artwork that she posts pseudonymously online. When curator Andrea Caulfield discovers Lex's work, she offers mentorship in exchange for control over Lex's career.

But as the pressure mounts, Lex's mental health deteriorates and Andrea seizes control of her work—leading Lex to orchestrate a psychological showdown against the mentor who nearly destroys her mind.

Thus, the film was always designed to contend with contemporary questions about art and ownership.

Why does that matter?

We did not employ technology as a cost-cutting measure or visual gimmick in Under the Influencer; rather, any and all tech leveraged in the film was as an intentional artistic choice to reinforce the film’s themes (in particular, those regarding authenticity, identity, and authorship in an increasingly digitized world).

Drawing from foundational concepts in art semiotics and performance studies (the basis of my undergraduate education at Brown University), I understand this film as a case where the medium itself becomes part of the message. Theorists like Roland Barthes explored how meaning is produced through layered systems of signs; Under the Influencer’s incorporation of AI (and other technological) elements creates a semiotic interplay between its narrative content and its means of production.

Essentially, the production methodologies become performative elements in themselves—invoking a key principle of performance studies: meaning is created not only through content, but via the means and context of that content’s presentation.

ON DRAWING (LINES)

In 2020, I decided to enroll in a master’s program in data science because I wanted to explore applications of AI and machine learning to creative disciplines.

In 2023, while actively editing Under the Influencer, I drew the line on AI use in TV and film as follows:

A U.S. Copyright Office declaration from January of this year seemed in lock step with my 2023 take.

In 2025, I am interested in AI as it pertains to filmmaking insofar as it:

Democratizes access for under-resourced and/or underrepresented filmmakers

Is thematically relevant to the narrative of a piece

Creates safety in dangerous circumstances (i.e. to obscure identity or ease the physical burden of an otherwise impossible stunt)

Does not infringe on performers’ rights

Avoids tools and systems that rely on unlicensed, copywritten training data for final creative output (the February 11th Reuters case ruling suggests this may be essential for anyone operating in this space)

Demonstrates consideration for the value artists add to our world

Other key points to start:

I do not advocate for the use of any particular AI workflow or tool, especially if associated with a company.

In my experience, I have found that AI video companies operate as much like gatekeepers as any legacy Hollywood studio. They handpick filmmakers and artists for special access and opportunities, often through unofficial processes. I have been invited to several “Creative Partner Programs”—while I am grateful for this access, I am not interested in generating short films and submitting them to AI movie contests for the rest of my life: I like live action films with humans, so I am grateful for access to tools insofar as the access supports me as I endeavor to do that.

In fact, wherever possible, and time/resource-permitting, I returned to sections of the film where I’d leveraged particular tools and substituted earlier work for iterations that instead relied on open source techniques (exceptions to this include specific tests/comparisons with some of Runway’s more filmmaking-oriented tools).

And even with open source tools come access issues: armed with 24GB of VRAM, I have labored for countless hours trying to coax my local ComfyUI implementation to process bits of cinema-quality footage.

One could test ideas in Krea or Kaiber or Luma before trying to replicate a similar open source process where there’s more control over data

The verdict is out regarding whether or not any of the new AI studios popping up can form and function successfully within a new paradigm.

I am not personally all that interested in purely generated images (still or moving). Rather, I am interested in artificial intelligence when employed as a stage in a process, or as a tool to transform or modify existing images. Exceptions to this include images generated from proprietary datasets fine-tuned for a particular purpose (a la LoRAs, defined and discussed later in this piece). Also, I have barely been able to make it through a film that was entirely AI-generated unless I was seated in a theatre for it—primarily because I cannot abide by lip-synced dialogue. It’s awful; it doesn’t work; I’ve never seen it be good. “But wait until __ months from now!” Nah. I will prioritize human actors until the end of time, forever and ever, amen.

I do not consider myself an “AI filmmaker.” It’s perfectly fine if you identify this way—no judgment. However, I am an actor, filmmaker, and data scientist who is open to implementing emerging technology in creative projects if/when appropriate to the work, and if/when it can be used with ethical consideration for other artists. I liken a single individual sitting behind a screen creating a film from end-to-end to a simulation designer, where the “humans” are avatars. That individual is world-building with avatars; I want to world-build with people.

THE MICROBUDGET

It makes very little sense to produce a feature-length motion picture for $62,000. Barring labor violations and low-key abuse, it’s also nearly impossible.

It is critical to note that our shooting budget was not $62,000 because of AI—on the contrary.

When I sat down to stitch together the footage we’d filmed using traditional live-action techniques, that $62K was long gone. The plan for post-production was always to have just me in the editor’s seat before handing the film over for final color and sound.

Why does that matter?

Because the AI testing and experimentation in Under the Influencer did not eliminate any jobs.

People are often surprised to learn that I wanted to make this film because I wanted to demonstrate the totality of what I can do as an actor. From day one of filming it was clear I would not be able to do that on this project. The circumstances under which we were operating were too challenging.

Instead, I used Under the Influencer as an opportunity to evolve as a filmmaker.

In post, when I encountered challenges that seemed insurmountable, I researched alternate possibilities and methods for addressing those problems and implemented them. Some of those solutions involved artificial intelligence; most did not.

Nobody really cares about the behind-the-scenes details of a tiny independent film. But we are (as far as I know) the first film of this kind to leverage this tech in this way, so I feel a responsibility to share—whether anyone cares or not.

Ninety-five percent of the AI use in the film, everything other than the process I developed for making the film’s art, emerged after the the completion of principal photography and pickups.

Why does that matter?

Because, in most cases—when a team has more than a few months to write a script and go into production (we did not, as we were bound by the conditions of a pitch competition we’d won)—good producing can eliminate a “need” for AI.

That doesn’t mean I think you shouldn’t plan to infuse AI into some part of your filmmaking process. You’d just better have a good reason.

NOTE: all GIFs included in the body of this piece are clips from Under the Influencer that have been severely compressed/degraded from their original quality and, in most cases, time remapped, to adhere to Substack file upload size limitations

THE HISTORY

For context, here are some key dates related to Under the Influencer’s production schedule as well as milestones in AI image/video generation.

EARLY SUMMER 2020

Producer Jill Bennett and I ask screenwriter Skye Emerson to work with us on a rough treatment. After a couple of meetings and some early sketches of ideas, we table the project.

AUGUST 2020

I start a master’s program at the University of Virginia’s School of Data Science.

2020-2021

COVID-19—and issues related to labor shortages, remote work technological needs, supply chains, productivity, and healthcare—is a boon to AI adoption, research, and advancement.

NOVEMBER 2021

We Make Movies selects Under the Influencer as one of the winners of its inaugural “Make Your Feature” competition. The project is a treatment at this stage.

FEBRUARY 2022

I begin work on the final project for my graduate Deep Learning course.

APRIL-JUNE 2022

I create the art for Under the Influencer.

MAY 2022

I graduate from the University of Virginia with a master’s degree in data science.

JUNE 15-30, 2022

Principal photography for Under the Influencer.

JULY 2022

Midjourney v3 released—it’s now in public beta with the first appearance of prompt-modifying parameters —stylize and —quality. The Midjourney Discord grows to 1 million users.

LATE SUMMER 2022

Early rudimentary tests and experiments with AI video processing.

NOVEMBER 3, 2022

Dall-E 2 in public beta.

NOVEMBER 26 & 27, 2022

Art gallery pickup shoot for Under the Influencer.

END OF 2022

At the end of 2022, there were zero publicly available text-to-video models.

FEBRUARY 2023

The release of Runway GEN-1, a model capable of applying the style and composition of a text or image prompt to an existing video.

MARCH 7, 11, & 12, 2023

Final pickups for Under the Influencer.

MARCH 28, 2023

Birth of the Will Smith eating spaghetti meme.

AUGUST 27, 2023

Neural Radiance Field (NeRF) shoot for Under the Influencer.

LATE SUMMER 2023

After Effects’ Roto Brush 3.0 released.

SEPTEMBER 11, 2023

Under the Influencer picture lock.

NOVEMBER 2023

Nathan Shipley & Paul Trillo’s written piece on AnimateDiff Motion Painting VFX.

DECEMBER 2023

Under the Influencer editorial conform, color correction, graphics, visual effects.

***Remind me to write a separate post about important things to consider in regard to codecs/format if you plan to upscale, change the frame rate of, or otherwise (p)re-process footage for a film project.

END OF 2023

Not a single one of the “AI Video Products” below existed at the end of 2022.

EARLY 2022 to MID 2024

I regularly contact RunwayML, PikaLabs, Topaz, Luma, and others about the film in hopes of securing support to (1) continue iterating and experimenting with new technology, and (2) hire artists to work with me to improve some of the special sequences in the film.

In 2024, PikaLabs makes initial contact asking how they can help; they never respond to my email nor my follow-ups. Producer Jill Bennett and I have a great meeting with Topaz; the company ghosts us following the meeting. Employees of Runway express enthusiasm about the film when I meet them in person at AIFF, but they never respond to any emails. Leonardo AI is responsive and awesome, but unfortunately, I have no need for their particular tool offerings (all primarily image-based) at this stage.

(I don’t share this to lambaste any particular company. Rather, I merely intend to demonstrate that I searched endlessly for additional resources to help me complete this film—both from traditional film finishing funds and from the AI companies supposedly invested in filmmakers experimenting with new technology—and that I simply didn’t get any.

Also, I can just hear the trolls now: “Maybe they didn’t respond ‘cuz your movie sucks!” Yup, maybe it does suck… But how would the aforementioned companies know?

Not a single one of them has seen it. Not a single one of them asked.

If Hollywood is a business of “haves and have nots,” AI-augmented Hollywood appears poised to follow suit.)

JUNE 2024

Luma AI releases Dream Machine.

JULY 2024

Under the Influencer final sound design, 5.1 surround mix. During this time, I rework several GVFX-aided transitions and the NeRF sequence.

AUGUST 28, 2024

First public screening of Under the Influencer.

JANUARY 2025

People are generating stuff like this out of nothing (well, not out of nothing… out of trillions of hours of illegally scraped video, oops).

THE ART

A few months out from production, the script wasn’t 100% finalized, but I knew we were going to need a LOT of art.

—Like, a lot.

—Enough to create an art portfolio sharing website for real…

—Enough to create a fake online gallery or two…

SO, a lot.

Initially, we’d intended to collaborate with an established artist and have that artist produce the pieces seen in the film, but—given our heavily truncated production timeline—we struggled to identify a good match.

It so happened that, in the spring of 2022, I was finishing my last semester of grad school at the UVA School of Data Science: enrolled in Data Ethics and Deep Learning courses while also completing a capstone project that used supervised machine learning algorithms to improve the visual classification of microscopic cell types.

SO, I decided I’d make the art.

I wanted to pursue an almost lo-fi, 2D aesthetic for Lex’s art in order to:

counterpoint the technological underpinnings of its creation

pre-empt potential future limitations as a result of our small budget

contrast the sterility with which some scenes were shot—which at times, to me, felt antithetical to the vibrating chaos of Lex’s interior/artistic life

invoke the concept of “flattening” or “flat affect”—a dulled intensity of emotional expression often associated with psychiatric medications

avoid boxing myself into a corner (I have worked for a visual effects company for the last year but not in a creative capacity. I’ve completed a VFX program through Warner Bros. Discovery, but the program focused on coordinating, not creative skills. I have long dabbled in AfterEffects and other software, but what few skills I have are limited to 2D work)

Once I had a sense of the art’s desired style, I developed the theoretical process by which Lex would create each piece.

LEX IS NOT AN “AI ARTIST”

In the growing discourse around AI art, there's been an frustrating misinterpretation of Lex's artistic practice in Under the Influencer.

While some viewers have labeled her an "AI artist," the film presents a more nuanced approach to her data-driven creativity.

The confusion likely stems from Andrea's description of Lex's work as "algorithmic generative art representative of her emotional struggles"—but this refers to something more intimate than text-to-image AI art generation.

What sets Lex's process apart from contemporary AI art (and associated ethical concerns about data sourcing) is that she works exclusively with her own data— specifically, detailed documentation of her mental health struggles.

This idea emerged from my own history: when I was first diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2015, I used an app to track my moods. Although I discontinued use of that particular app in 2016, I imagined how much data I’d have amassed had I persisted: approximately 100,000 rows, plenty to manipulate for meaningful artistic visualization.

AI art raises ethical red flags due to the unauthorized use of training data scraped from other artists' work, but Lex's artistic practice is deeply self-referential. She’s not feeding text-based prompts into an AI system—rather, the computer ingests her disordered data and self-portrait-style photo inputs before re-processing and re-presenting them as direct expressions of her lived experience.

The "algorithmic" nature of Lex’s work comes from how she systematically transforms her personal psychological data into visual art through both digital and traditional means. It's a hybrid practice that begins with her own emotional metrics.

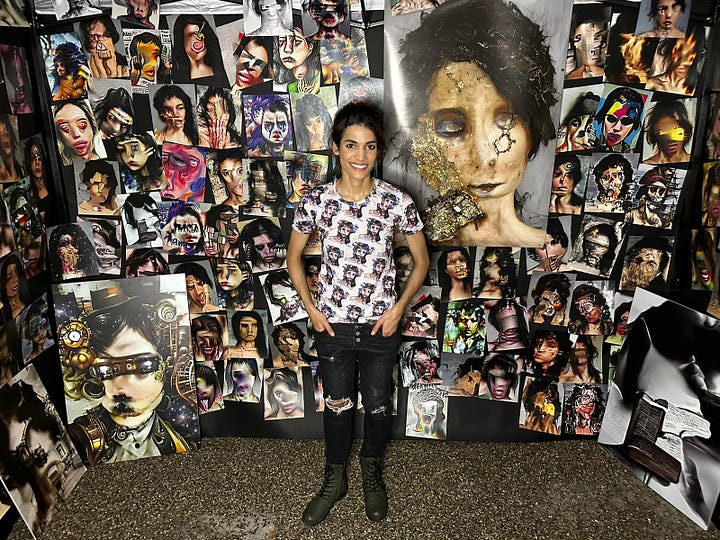

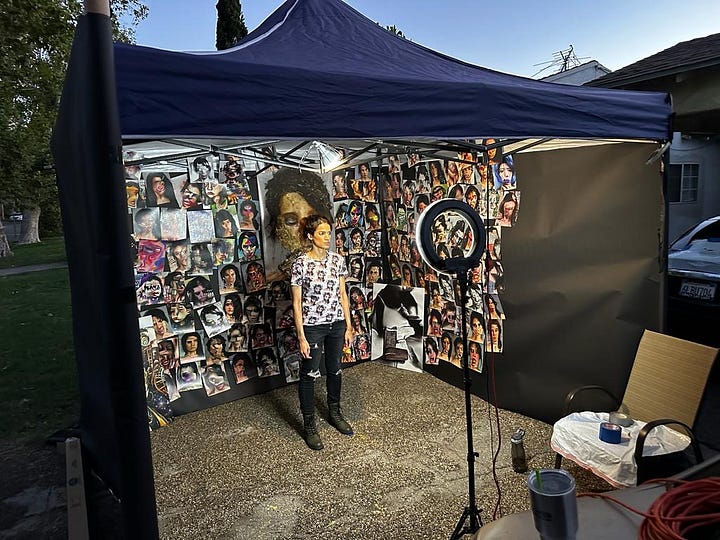

The film shows her workspace filled with physical paintings and illustrations alongside digital tools, emphasizing that her creative process spans both analog and digital realms. Lex creates a visual language from the data of her own psychological landscape.

One of the most irritating outcomes of the AI art boom has been a cheapening of other types of technology-infused art in the public consciousness. Artists have long experimented with technological processes—unfortunately, much of this experimentation is now immediately conflated with text prompt-based generation.

Arguably, Lex’s process is a MORE visceral, LESS mediated methodology for experiencing the raw power of her emotional interiority—color, shape, and pattern exploded by the raw data of her moods and anxieties.

The Art as Art

The art “as art” was the only use case for machine learning, deep learning, and/or artificial intelligence that was preconceived and executed prior to production.

I started with 144 self-portrait-style photographs of my face.

While I’d committed to making the art for the film, I did not have time to develop a pipeline to do the work via “Lex’s process” as I’d defined it. Mostly, I knew I did not have time to reset, regroup, and restart the process over again if the first outputs weren’t usable or if there were issues with my pipeline.

As previously noted, in spring of 2022, as we barreled into pre-production, I was finishing my final semester of grad school, enrolled in a Deep Learning course. For our final project, my classmates and I had elected to research and explore GANs, or Generative Adversarial Networks.

We tested the efficacy of training models on non-artistic data sets to dupe survey responders into thinking that humans had created artworks that had in fact been made by computers.

Our research demonstrated that models pretrained on non-art subjects (i.e. cat faces, dog faces, breast cancer cells) could generate convincing artwork through transfer learning, reducing training time by 65% while improving quality metrics.

Notably, a model originally trained on feline facial recognition proved effective at generating convincing art, with one particular output fooling 83% of our survey respondents into believing it was human-created.

VFX Supervisor Peter Gagnon trolls AI-related posts on LinkedIn, regularly posting the comment, “Where’s the data from?” He’s right to ask; it is this question, the source of AI training data, that forms the basis of the most robust opposition to generative artificial intelligence.

It was the philosophical underpinnings of his question, coupled with my graduate Deep Learning research, that inspired me to explore using non-human datasets as style inputs to transform the original 144 photos—beginning with those same feline faces, wild animal features, canine portraits, and microscopic imagery of breast cancer cells from my GAN project.

I eventually expanded the style source material to include datasets of pure textures and materials, then to include similar datasets of all sorts. This facilitated the integration of complex textural elements while maintaining recognizable facial features.

In some ways, I was blind to the looming controversy regarding using others’ art/films/etc. for training data because, at first, I was thinking about the experimental aesthetics that could be borne of “non-artistic” data.

For pieces featured prominently in the film, the GAN-processed outputs served as a foundation for further refinement. Through traditional digital post-processing techniques (i.e. Photoshop), I enhanced elements, eliminated artifacts, and adjusted color compositions.

Not every resulting artwork was successful—there is a reason only a few, manually cleaned up pieces are heavily featured in the film. However, I appreciated this outcome because it more accurately reflects what would have happened had I mirrored “Lex’s process" exactly.

ACADEMIC BACKGROUND

Style transfer architectures highlight a key ethical distinction in AI: using pre-trained models as feature extractors versus generators. A basic neural style transfer system uses two networks: a pre-trained feature extractor (trained on potentially unlicensed data) and a transfer network trained from scratch (note that not every style transfer system functions identical to that which I am summarizing here).

The pre-trained network acts as an analytical tool—its layers have learned to decompose images into content features (shapes, positions) and style features (textures, patterns). By comparing these feature activations between images, we quantify style and content similarities. While it doesn't directly generate images, its feature representations guide the optimization process.

The image transformation happens in the transfer network, which has an encoder-decoder architecture trained specifically for style transfer. During training, style and content images pass through the fixed pre-trained network to extract features.

The transfer network learns to produce stylized images that match these feature statistics, with its weights being the only ones updated. The loss function balances content preservation against style matching by comparing extracted features from the output image against those from the reference images.

MERCH

In Under the Influencer, protagonist Lex's art is packaged, printed, and sold without her consent. I created a legitimate merchandise line that mirrors this plot point using only the artwork I’d already made for the film and trusty ol’ Photoshop.

The collection of wearable pieces includes:

Crop tops with all-over art prints

Bomber jackets and t-shirt dresses incorporating patterned versions of the original portrait-based designs

Sports bras, athletic wear, and fanny packs

The designs deliberately incorporate the artwork in ways that blur the line between fine art and commercial products, echoing Andrea's exploitation of Lex's work.

In the film, extended onslaughts of digital assets featuring these products demonstrate how influential individuals leverage their platforms and reach to exert sociological and psychological pressure on others.

We made these items real and purchasable through www.undertheinfluencer.art, allowing the merchandise to function both as authentic props and actual products.

Selling merchandise in the physical world creates a purposeful tension between criticism and participation, simultaneously (1) inviting audiences to examine their own relationship with consumerism and social media influence, and (2) making viewers both observers and participants in a dynamic the narrative seeks to explore.

All funds raised provide practical support for the film’s continued promotion and distribution.

OTHER ART

Myriad artworks not attributed to Lex/Neomy appear in the film. Some were sourced from visual artists Cristina Platita, Shelley Bruce, Tami Lane, and Michelle Reyes.

Others were the result of further experimentation with my own photographs.

As previously noted, all of the above—the art as art—was my only pre-planned experimentation with AI.

The Art as Character

When Assistant Editor Jack Horkings first reviewed our footage, he pointedly asked, "Where's the art? This movie is about art, and I'm not seeing it… Where is the art?”

He was right.

Since 2010, Jack has been my best friend, creative confidant, and artistic soulmate—there are few opinions I value more than his when it comes to art.

And he was right.

The art needed to feel like another character in the film—it needed to map the trajectory of Lex’s mental state.

Aesthetically, the film itself needed to resemble a work of Lex’s art; energetically, its pulse needed to emulate the mania of her creative process.

Philosophically, Under the Influencer needed its audiences to wonder where the artist ends and her work begins, and how much suffering is warranted in its creation.

Otherwise, what were we even doing making this film?

This was no longer about creating individual pieces of art—it was about making the entire film feel like one of Lex's works. In spite of having created hundreds of pieces of art (and despite having used that art for production design, digital assets, wardrobe, etc.), the film hadn’t yet captured an essential quality that was a key justification for telling this story in the first place.

Jack’s feedback launched an all-consuming, obsessive quest to inject the Lex/Neomy art into the film’s DNA. The mission began in July of 2022—and for the next two years, this undertaking ate me alive.

We conducted two additional pickup shoots totaling five days to better integrate the artwork into the narrative and deepen character development. But the real transformation happened in post-production, where we began to treat every frame as a potential canvas for Lex's artistic expression.

Arguably, it is also this work that has elicited the most enthusiastic responses from audience members.

The meta-textual implications are impossible to ignore: an actor playing an artist, that actor creating the artist's work via a process that involved some AI, in a film about art and identity that itself becomes increasingly artistic in its presentation.

The boundaries between character, actor, artist, and creation became deliberately blurred, adding depth to the film's exploration of artistic authenticity and ownership.

DATAMOSHING

JK, this ain’t AI at all!

The use of datamoshing in Under the Influencer operates in multiple dimensions of meaning. As Lex transforms her “emotional struggles” into artwork, the film deliberately corrupts its own digital flesh through relatively ancient datamoshing techniques (primarily rendered in AfterEffects).

The datamoshing sequences, complete with bleeding and fracturing and dissolving pixels, illustrate how Lex's artistic practice distorts her lived experience. These moments of digital disruption—where the film appears to be eating itself—reflect the cannibalistic nature of using one’s life as the raw materials for one’s art.

Just as Lex's artistic process involves fragmenting and computationally reanimating her experiences, the datamoshing physically deconstructs the film's frames, making visible the compression artifacts and glitches we typically endeavor to hide.

The seams and corruptions in the datamoshed stretches serve as a reminder that some piece of Life will be distilled or destroyed in any attempt to render it as Art.

These moments represent a kind of liminal space between experience and expression, between living and creating, between being and performing—a recursive loop cycling between form and content.

Datamoshing’s degradation of the images adds another meta-layer, a kind of messiness not unlike the physical act of applying paint to canvas. This stands in contrast with the overproduced images of contemporary social media algorithms and aesthetics—not unlike the contrast between Lex's psychological self-portraits and Andrea's curated gallery glam.

MOGRAPH

Due to circumstances outside of our creative team’s control, the post-production services company originally slated to create our titles, credits, and motion graphics reneged on its promises to us weeks before a deadline, so I assumed the responsibilities.

While far from ideal, this hiccup enabled me to ensure that themes of online identity and artistic manipulation extended into the film’s motion design elements (to the best of my ability).

One example—Andrea illuminated in dramatic lighting while engaged with a mobile device—is composed to emphasize the interface between human and digital realms. The windows and arched doorway create a frame within a frame within the frame, suggesting layers of heavily mediated reality and representation.

As Andrea endeavors to tag Lex’s deleted social media accounts, the motion design elements distort and deteriorate via standard analog glitch techniques (no AI).

EXPERIMENTAL WORKFLOWS

The visual development of certain scenes (i.e. scene 16, included below) required pushing beyond traditional filmmaking approaches to capture Lex's artistic process in a more experimental way.

Production captured a single, slow push-in dolly shot of Lex working at night—I saw an opportunity to transform this limited footage into something more evocative of her creative mindset.

Drawing from the same neural style transfer techniques used in still art—only this time using single-image neural style transfer as opposed to working with different datasets—I processed the original footage into 15 distinct versions.

The method involved isolating different portions of each frame and applying style transfers derived from sections of Lex's artworks.

By combining these processed versions through traditional editing techniques, the resulting sequence achieves a more nuanced portrayal of her artistic process than the original footage alone could provide.

While newer developments in Animated Diffusion and inpainting technology would have offered creative possibilities of a less patchwork variety, this experimental approach helped transcend the limitations of the source material to better serve the story's needs.

I employed a similar process in sections of two other key scenes.

SHADOW LEX

What started as unplanned footage in a dark garage—filmed at producer Jill Bennett's insistence—became the frame for our entire narrative.

In the film's opening, we see Lex both emerging from and being swallowed by shadow, initiating a transformation that's simultaneously chosen and forced upon her.

I re-processed this section of the film a dozen times using selected works of Lex’s art as init (starting) images. Through blended layers of neural style transferred-video, AfterEffects rotoscoping, and AI-assisted masking, we watch as something both internal and external manifests—luminescence and shifting patterns suggest something otherworldly taking form, a version of Lex capable of executing what needs to be done.

When we return to this imagery in the film's final moments, it carries the weight of everything that's transpired.

Shadow Lex, having kept Lex vigilant and focused through the pivotal confrontation with Andrea, now retreats back into the darkness—her mission of artistic revenge complete.

The same technical processes that chronicled her emergence are absent in her recession—although we may summon a dormant darkness for survival or justice, we needn’t remain in that state in perpetuity.

Shadow Lex represents the power that artists deliberately call forth and the changes forced upon us by trauma. In the film’s concluding frames, as Shadow Lex steps back into the darkness, it's not a defeat but a completion—Lex making a deliberate choice to return to herself… now that justice has been served.

What began as serendipitous pickup footage became a vehicle for one of the film's core ideas: sometimes we're both the architect and victim of our own metamorphosis, both the artist and the raw materials.

END (AND START) WITH ART

I’d always wanted the film to start by propelling the audience into the art.

The script itself outlines the audience’s introduction to Lex in this way:

Still, there was no specific creative vision for the film’s opening established during pre-/production, so how this would be brought to life in the film fell to me.

During our second pickup shoot, I collaborated with Director of Photography Rachael Hastings Adair to grab unusually long inserts of screens specifically for this purpose.

The audience moves into the screen on the z-axis, through a liminal gallery space, through shifting polygons, until we arrive at Lex’s face—as if Lex is born of her art. As if the promise of Under the Influencer is to, for 100 minutes, stand Lex’s lo-fi work on its feet and let the audience inhabit it in three dimensions.

I thought I might be able to achieve something like what I was envisioning for “the birth of Lex” by starting with the opening frame of Lex’s face, processing it through an img2video (image-to-video) system, then playing the video in reverse.

Through much of 2022, I’d experimented with diffusion animation in all of its iterations (i.e. Deforum). I started to run implementations of Automatic1111 and, later, ComfyUI on my own PC.

A paper originally published on LoRAs (Low-Rank Adaptation) in 2021 had a resurgence when it found its way to GitHub in late 2022 and this proved monumental—with LoRAs came the ability to fine-tune diffusion models on small annotated datasets. With the advent of LoRAs came the ability for just about anyone to train a model on only their own legally sourced data, with dramatic improvements in model training efficiency (and, therefore, less need for computational resources).

Soon, I was able to research best practices, methods, and LoRA training tips thanks to a robust community sharing its many tests and experiments. In particular, I was excited by the ability to merge LoRAs (either multiple LoRAs together or with full pretrained models) and interpolate between the fine-tuned models themselves.

Why?

On the surface, LoRAs sound like the answer to our data ethics prayers: a manageable, comparatively microscopic dataset providing greater control over image/video output. However, many LoRA use cases involve merging a LoRA with a pretrained model.

So yes, one may be finetuning the model using their own proprietary data, but ultimately, the process could still rely heavily on some version of Stable Diffusion or another of the foundational video models. Many LoRAs available for public download and use also do not disclose the source of their training data.

Training custom LoRAs on curated datasets of variations of our lead characters’ faces allowed these models to operate like a single syringe injected into the DNA of a larger digital canvas.

The animation flow was choreographed to pull viewers through layers of abstraction—starting with simple geometric forms that would morph and interweave, leading into a liminal gallery space where reality and art coexist. The sequence culminates in the revelation of Lex's face emerging from her own artwork.

By interpolating between models, I could create fluid transformations that feel at once mathematically precise and organically artistic. Similar techniques, reversed and recontextualized, provided a fitting bookend for the closing credits.

META MOTION

There's something profoundly recursive about using AI to animate AI-injected art that was itself derived from original photographs, while simultaneously embodying the character these images represent. Each layer of reprocessing and transformation adds new meaning while maintaining a connection to the source material, creating a kind of dialogue between physical performance, static art, and the animated iterations.

Movement gives the art permission to express itself beyond the constraints of a single, still moment—not unlike how embodied performance allows an actor to explore character beyond the constraints of the written page.

The most ethical workflows for this involve training LoRAs on proprietary datasets to finetune motion in ComfyUI, as most out-of-the-box image-to-video tools have been trained on unlicensed data. If using such a tool, at what point does adding motion to one’s own image cross an ethical line?

Can one address concerns by being extremely selective, only using outputs that manipulate existing elements within the art (rather than those that introduce new visual content and change the material nature of the image)?

The Art as Plot

CREATIVE INTERPOLATION

Specific transitions use iterations of Lex’s artwork and ComfyUI Frame Interpolation to externalize Lex’s psychological journey.

To do this, I captured stills from the film, manually degrading and altering many in Photoshop, then incrementally interpolated between them. In the case of the examples below, I also toggled between traditionally shot footage, stills from that footage, and the image files for Lex’s artwork itself—as each transition documented here centers on a particular piece of art.

In the first transition—created by interpolating between eleven stills—image and identity shatter simultaneously. The split-screen of Lex and Andrea breaks into progressively smaller pieces until both the characters and film’s title dissolve into digital artifacts. These pixels—fragments of Lex's disintegrating self—reconstruct themselves into the "Release" artwork (attributed to Neomy, Lex’s pseudonym) on Andrea's monitor. The visual decay mirrors Lex's psychological splintering under Andrea's influence.

The second transition presents an almost hypnotic ECU of an eye. Starting deep within Lex's artwork—literally inside “her” eye—we ratchet back through layers of artistic consciousness.

The original idea for the art wall was producer Jill Bennett’s, and the idea was always meant to involve an ECU on a piece of art. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, we didn’t get it—he shot didn’t exist: we didn’t actually capture anything from that tight on that art.

So I basically…interpolated my way to a manufactured version of it.

As the camera retreats, we see this intimate detail is part of a larger piece, then further still until her work engulfs the gallery wall. Lex sits amidst it all, her internal landscape now externalized, her private pain made overwhelmingly public.

Both transitions use technology to visualize psychological transformation; the frame interpolation adds an uncanny quality to moments of artistic metamorphosis.

BANODOCO & STEERABLE MOTION

By summer of 2024, when I was able to revisit and rework these moments in the film, multiple versions of the highly effective Steerable Motion workflow had been released, which I found extremely useful for my purposes.

For Steerable Motion itself and support using the Steerable Motion workflow—as well as for the help, inspiration, and/ or ideas I needed to do so much more—I credit and offer endless thanks to POM and the Banodoco open source AI community.

NEURAL RADIANCE FIELD (NeRF)

The Neural Radiance Field rooftop sequence crystallizes the film's core exploration of reality versus artifice. We move from Andrea's documentary-style confrontation—complete with visible camera metadata—into a swirling vortex of Lex's artistic consciousness.

The NeRF implementation arose from—surprise!—a need to solve a major problem: the entire middle section of the scene, the film’s climax, simply did not work as shot. It sagged and slowed what should have been rapidly rising tension and friction.

After hours of trial and error in the edit, producer Jill Bennett and I concluded that we had to excise the middle of the scene. Once removed, the scene played infinitely better; however, now I had to figure out how to bridge the opening and concluding thirds of arguably the most important scene in the film.

Thank you Jake Oleson for convincing me to act on my burgeoning obsession with neural radiance fields.

The Neural Radiance Field captures Lex's psyche shattering in real-time. Shot on the summer's hottest day, the reconstruction maps hundreds of photographs onto a psychological space where every artwork represents a different version of Lex—past works, abandoned attempts, future possibilities, all existing simultaneously.

"You're not real, none of this is real!" Andrea declares as she pushes the camera, initiating the rooftop’s physical metamorphosis into an abstract psychological space.

The NeRF reconstruction allows us to move impossibly through a kind of “gallery of the mind” where mental health (or disorder) curates Lex’s self-concept.

After setting the NeRF camera path and speed ramping the sequence appropriately, I re-exported the ~8-second stretch as individual frames—approximately 200. I then upscaled, sharpened, and (via Photoshop) selectively altered every single frame to produce a dizzying hall of mirrors—Lex infinitely reflected through her own flickering iterations of self in a moment of crisis.

The technical process mirrors the psychological: just as the NeRF reconstructs 3D space from fragmented 2D images, Lex attempts to reconstruct herself through her art. The swirling chaos of color and motion represents both breakdown and breakthrough— every frame a new painting, every painting a new self, culminating in a piercing close-up of the Artist’s Eye before Lex emerges—almost as progeny of Andrea—with a challenge: "You wanna see something real?"

The NeRF integration transforms what could have been a conventional confrontation into a meditation on authenticity in an increasingly synthetic world. Each generated viewpoint and impossible camera move questions not just what is real, but whether that distinction still matters in an age where technology can reconstruct reality with near-perfect fidelity.

The sequence transforms a kind of documentary reality into a neural-generated representation of fractured identity, where the distinction between artist and artwork, real and artificial, original and iteration collapses into a singular moment of crisis and transformation.

The NeRF was in place by the time I picture-locked the film in September of 2023.

In 2024, when I was able to revisit and rework certain effects, transitions, and short sequences of the film, I contacted Luma AI several times with a proposal for partnership: I asked for any kind of support (marketing, monetary, knowledge, access, tools, etc.), the idea being that the NeRF could be made infinitely better with more resources and expertise.

Luma did not respond to any inquiry or request.

THE INVISIBLE

SECRET MVP

Thanks to our wonderful contacts at Sony, we primarily shot Under the Influencer on the Venice, in 6K X-OCN. However, due to the realities of microbudget filmmaking, we had to use three additional cameras at various points in the process (BMPCC, Sony a1, Sony FX3).

Knowing that we would be already be contending with various codecs and file formats contributed to my decision to take whatever liberties necessary to finish the film to the best of my ability.

This included an executive decision to use Topaz Labs’ suite of AI-powered tools to upscale and change the frame rate of some footage.

GLORY TEAR

In this case, we captured a genuine moment—falling tears that embodied Lex's emotional state—but the timing wasn't ideal. The most visible teardrop fell during a moment when the camera was rolling, but not in the sacred time between “Action!” and “Cut!”—and just as I made an unplanned head movement, which would typically make the moment harder to read on screen.

Using Topaz’s frame interpolation tech, I took the original 23.976fps footage and transformed it into 120fps. This allowed me to slow down the sequence significantly while maintaining visual clarity, giving the audience more time to register the tear. The software's ability to generate intermediate frames meant I could stretch this moment without introducing the stuttering and artifacts typically associated with slow-motion conversion (but please: ignore the stuttering and artifacts introduced by my conversion of this moment into a GIF for the demonstrative purposes of this written piece).

Topaz’s upscaling tools also came in handy elsewhere.

S’AH-CURE-IT-EE

Because we shot at my best friend's house, I was able to access years of archived security camera footage thanks to his meticulous digital hoarding habits. This opened up a fascinating creative opportunity—I could incorporate authentic surveillance footage from an actual shoot location into the film.

I used AI upscaling to enhance the CCTV footage while preserving inherent surveillance qualities (i.e. scan lines). The footage shows the exterior stairs, pool area, and various angles of the property from the house's actual security system.

The fact that this isn't simulated CCTV footage makes it hella more compelling—it's IRL security camera material showing mundane, unperformed moments from the same spaces where we filmed.

I don’t know what’s scarier… the privacy invasion, or the fact that I probably read 4-5 books with titles like “The Aesthetics of Surveillance” in college.

TO THE ROOF

The script called for two tense scenes showing Andrea's journey from downstairs to the roof after receiving a security alert—an essential, suspense-building moment immediately preceding the film’s most climactic scene.

However, due to time constraints during our only overnight shoot, these scenes were never properly captured.

The only available footage consisted of a handheld iPhone recording of actress Erin Matthews walking up stairs, filmed off a security monitor, and a single blurry reflection of Erin walking up house stairs, captured incidentally in the corner of another shot while cast and crew reset.

To create scene 70, I upscaled the shot of Erin walking upstairs to 12K; I increased its frame rate to 120fps. I upscaled and slowed a number of the other shots in the sequence as well.

Ideally, we would not have seen Andrea’s outdoor stair ascent mediated through a security monitor, but that was our only option.

Thanks to Topaz and Jack’s stockpile of home security footage, at least we didn’t need to watch this via the iPhone-filmed clip.

A LITERAL RE-FRAME

On set for another scene, I was directed to “discover” the framed photo of Andrea on my line, but it never felt natural to manufacture that discovery out of thin air. It was also not how the moment was originally scripted.

Every take where I simply turned my head toward the photo on “to her” felt forced, and watching these takes back in editing confirmed my instincts.

Instead of accepting those versions, I endeavored to recreate the moment as scripted: with Rachel glancing at the photo, the glance giving away the photo’s significance. However, at no point during filming had we shot the scene as scripted; we did not have a single shot of Rachel looking toward the photo of Andrea on the desk.

I found a solution in the footage we had: a quick shot of actor Joy Sunday glancing away from the photo. By slowing down this clip to 120fps and reversing it, I created what I needed—Rachel registering the framed photo. This gave Lex something real to react to, rather than trying to conjure surprise from nothing. Rachel’s subtle eye movement became the perfect lead-in for my character's discovery, making the whole sequence feel more natural.

Rather than requiring costly reshoots, the manual upscaling and frame rate adjustment process offered a way to preserve intended story beats while working within the limitations of existing footage.

While using a tool like Topaz presents its own challenges—including subtle artifacts from AI upscaling, significant rendering time at high resolutions, an extended trial-and-error period to determine the best export settings for each instance, and a massive headache for our colorist—it is viable, ethical option for addressing issues of this nature.

THANK YOU, RACH

Our DP had first right-of-refusal for any and all post-production shifts in frame rates and adjustments to how shots were originally framed.

Fortunately, Rachael Hastings Adair is a generous and conscientious cinematographer—she is also well-versed in low-to-no budget production. Thus, she understood that any changes I made in post-production were simply to support the film’s narrative and overall final product.

I would not have done what I did in post-production without her blessing, since it was ultimately her work on the line.

Between upscaling in Topaz and pushing in on the 6K Sony Venice footage, I estimate that ~80% of the shots seen in Under the Influencer were manually reframed.

THE UNCONVENTIONAL

AFTER EFFECTS ROTO BRUSH 3.0

While we hired visual effects artists to complete most screen replacements in the film, Adobe's Roto Brush 3.0 tool made it possible for me to tackle this composite despite not being a professional VFX artist. The AI-assisted rotoscoping helped isolate the phone's screen while maintaining clean edges around fingers and accounting for subtle movements.

After establishing the base mask, I refined the edges and adjusted the feathering to match the natural motion blur of the original footage. Adding motion blur and reflections to the replacement footage helped sell the effect.

BRIDGING A GAP

The Sixth Street Bridge sequence presented an interesting challenge: how to create a moment of psychological terror where our protagonist encounters a shadowy version of herself.

Though I'd initially hoped we’d capture rapid, disorienting camera movements on set—and specifically requested whip pans—, we didn’t get them, so I had to pivot in post.

In this instance, while I was prepared to work in AfterEffects, I wanted to continue to test the efficacy of RunwayML's masking tools to isolate figures and composite multiple versions of Lex into the nighttime scenes.

I used Runway to create separate mattes for each "Shadow Lex," allowing me to blend these figures into the moody bridge lighting.

The final sequence has a different kind of unsettling energy than what might have been achieved with whip pans, as the limitations of our original footage pushed me toward alternate solutions. Instead of rapid, jarring movements, we got something more subtle—shadow versions of Lex seeming to materialize from the darkness itself, wearing her art like masks.

While Runway’s suite of tools isn’t robust enough to replace any part of a traditional VFX (or even a basic AfterEffects) workflow, it provides a middle ground for under-resourced filmmakers who need to achieve effects without extensive VFX experience.

VFX PREVIS & MOCKUPS

When I say “I used AI in the making of this film,” I also mean as a sort of helper—as a way to test, as a method for iteration, as as intermediary step.

The mirror shot presented a visual effects challenge—creating a seamless composition where the reflection shows a subtly different reality than what's in front of the mirror.

While we ultimately hired a professional VFX artist to execute the work for the final shot, RunwayML's tools proved helpful in the pre-visualization phase.

Testing RunwayML's green screen and masking capabilities, I quickly mocked up different versions of how the shot might look. The software's AI-assisted masking imperfectly but sufficiently separated the foreground elements from the background, allowing me to experiment with various ways of compositing the mirror's reflection.

This rapid prototyping approach helped me nail down exactly what I wanted before engaging an artist. The rough comp served as a crucial visual reference; there was no need to try to describe the desired effect via verbal or written language.

THE FUN

ADOBE GENERATIVE FILL

Per my guidance (and best estimation of how I would eventually execute this), screenwriter Skye Emerson initially wrote “3D Lidar” via Polycam into the script; however, after AE Jack Horkings performed some initial tests, he and I decided to scrap that route.

Here, Lex taunts Andrea by sending her a voyeuristic photo of Andrea in the bathtub. It’s scary enough to imagine someone snapping this and sending it to its subject moments later; the scenario is more unsettling thanks to Adobe’s generative fill.

In this pivotal scene, generative AI technology serves both narrative and thematic purposes. The scene shows Lex psychologically manipulating Andrea by sending her an artificially extended image of herself in a vulnerable moment.

The horror stems from multiple layers: first, the violation of privacy implied by someone capturing an intimate moment; second, the technological implications of how the image was created. The idea is creepy enough that it almost always elicits uncomfortable chuckles from audience members.

The ability to generate photorealistic images of people in situations that never occurred raises questions about consent and authenticity. By using generative fill to create this moment, the film suggests that traditional markers of truth—i.e. photographs—can no longer be trusted as evidence of reality.

The technology also reinforces the power dynamic between the characters. Lex's ability to manipulate Andrea's image without physical access to her demonstrates a form of control that transcends physical boundaries, making the psychological torture more insidious.

THE DISCARD PILE

As one can imagine, I tested all sorts of things as potential problem-solving solutions over the course of 2+ years enmeshed in this process.

Ultimately, much of what I tried I was not prepared to use, primarily because there was no creative imperative that outweighed my ethical concerns.

THE UN-DISCARDED

None of the following involves any artificial intelligence—not even any newfangled technology! The most effective “movie magic” will always come from traditional filmmaking ingenuity and creative problem-solving.

These approaches are not revolutionary, but they offered unique solutions to our creative challenges and helped define the film's visual language.

NON-STANDARD EDITING PRACTICE

My post-production process involved pulling from the fringes of raw footage files (anything captured prior to “Action!” and after “Cut!”) in order to:

create a sense of movement and space

compress and expand time

heighten emotionality and audience identification with character

visualize a moment we’d otherwise not have captured

create entirely new plot elements

leave little Easter eggs

deepen a character’s arc

CONCLUSION

FURTHER EXPLORATION

If your interest in AI is similar to mine (that is, you are a filmmaker interested in practical use cases and creative problem-solving when operating with limited resources), follow individuals like Purz, Jon Finger, Paul Trillo, and Nathan Shipley—artists who are experimenting and sharing their processes with an eye toward ethics. Engage with communities developing for and working with open source methods.

I am tentatively excited by the promise of entities like Asteria Film Co, which is hiring some of best creative AI minds while training a “clean” video model.

I recommend testing the latest tools from the “big few” AI companies so you know what’s out there, but I caution against believing most of their philosophical lip service at face value, as their success ultimately hinges on paying customers using their tools as prescribed.

VALUE PROP

Filmmakers, creatives, and audiences alike are welcome to find value in Under the Influencer—or not.

If you categorically reject Under the Influencer because the film uses some AI technology, that is your prerogative and right. The film was not meant for you.

If you reject Under the Influencer because you don’t think it’s successful as a narrative motion picture, that is your prerogative and right. The film was not meant for you.

If you are someone who watches movies and assumes that whatever ended up on screen is exactly what the film’s author(s) wanted to be there, you probably don’t have a lot of experience with microbudget films.

FAQ

Do you really think anyone is going to read this entire thing?

Nope! Still, the historical record ought to exist.

Was Under the Influencer copyrightable under U.S. Copyright Law?

Sure was.

What roles did you formally occupy on Under the Influencer?

Technical Director, Editor, Executive Producer, “Lex”

Those credits seem a bit unconventional…

They are. After picture lock in September 2023, our ‘core creative’ team of five met to discuss any yet unacknowledged contributions to the film. The team decided that my labor warranted an additional title—the film’s Director suggested the language “Technical Director”

So, while only one Director was responsible for helming scenes on set, it is also inaccurate to say that this film was singularly authored by one individual. Under the Influencer was not a co-directed project, but our team considers both Director and Technical Director authors of this film.

How is the role of Technical Director defined in the context of this production?

Including but not limited to: all of the text above.

Anything else we should know about the film?

Under the Influencer was the proof-of-concept for producer (and my wife) Jill Bennett’s low budget production model, Fair Play Films

Where can I see Under the Influencer?

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA: Wednesday, February 26th @ 7p (Queer Screen’s 32nd Annual Mardi Gras Film Festival)

PERTH, AUSTRALIA: Friday, March 7th @ 7p (9th Annual Perth Queer Film Festival)

GILROY, CA, USA: Saturday, April 12th @ 4p (Poppy Jasper International Film Festival)

UPDATE LOG

Monday, March 17, 2025: Updated The Art as Art section to include direct mention of and link to VFX Supervisor Peter Gagnon, who read this piece and gave his permission for use of his name.

This is an amazing resource Lauren!

What a fascinating write-up. I'm amazed that those AI companies all (unless I misread?) ghosted you. It seems like it'd be a no-brain involvement for them. Don't they all want to get into the hands of major studio players? Odd. Really cool to see how you upscaled resolution and frame rate in order to manipulate things in the edit. I already knew about your more flashy use of AI in this film, but it was cool to see how you used it to facilitate those more invisible changes. I really appreciate this post, Lauren, and I can't wait to see what comes next from you.